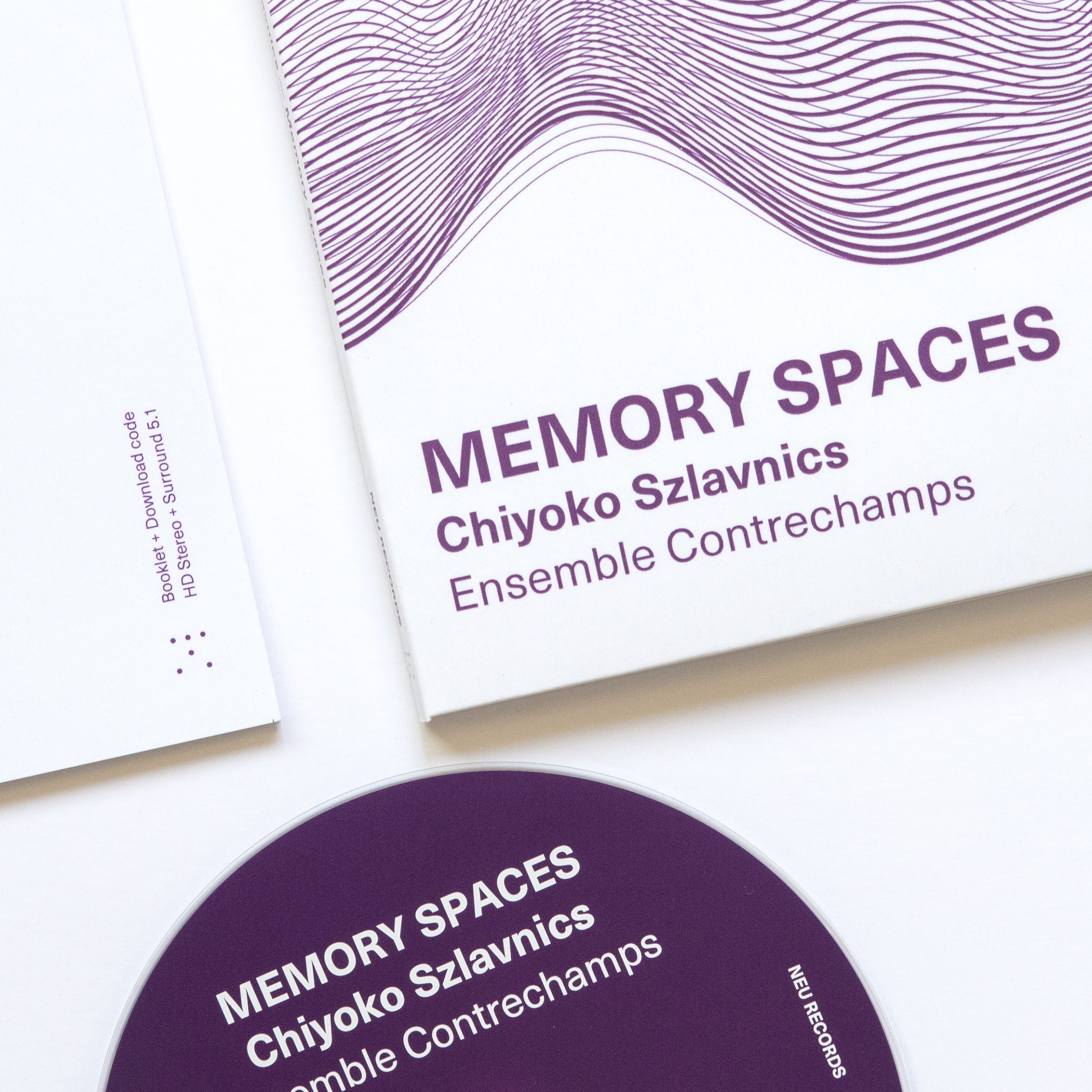

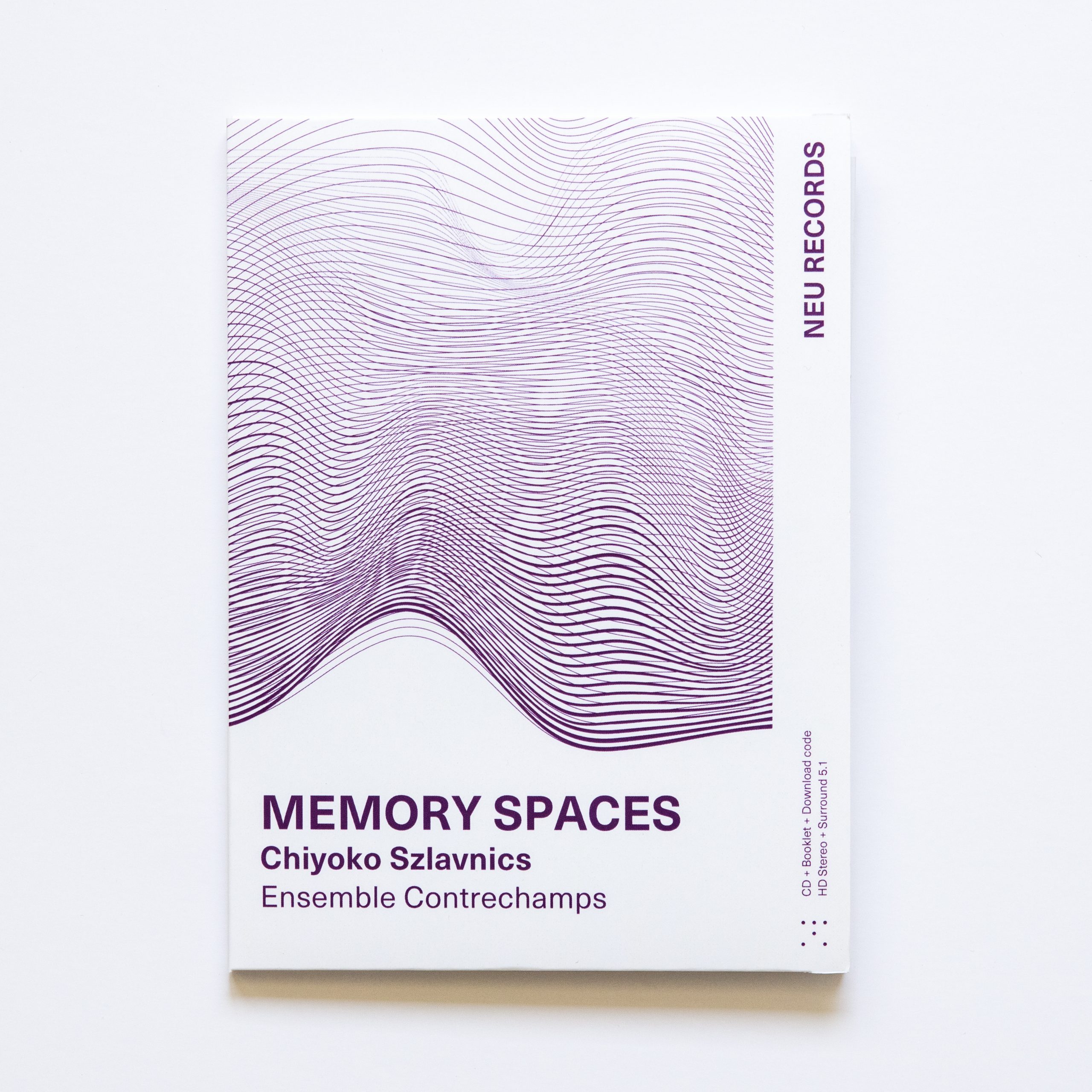

MEMORY SPACES

Ensemble Contrechamps

NEU RECORDS

Chiyoko Szlavnics

Ensemble Contrechamps

Max Murray, conductor

1. Memory Spaces (appearances)

for fourteen stringed instruments (2017, Rev. 2023) 20 min.

2. For Eva Hesse

for electronics (2006) 14 min.

3-7. Oracles I-V (listening spaces) *

for 20 instruments (2020, Rev. 2023) 39 min.

* World Premiere Recording

Total time: 73:42

Recorded in 3D format (Dolby Atmos 7.1.4), surround sound (5.1) and stereo (2.0)

BUY ALBUM

CD + Booklet — HD Digital format included — 21,90€

HD Digital — Stereo and Surround 5.1, 24bit 96kHz — 14€

Digital — Stereo, 16bit 48kHz — 10€

More info about formats here

Also available on Bandcamp [HD Digital].

Combinations Tones

The recordings gathered on this release bring together two ensemble works for acoustic instruments by Berlin-based Canadian musician-composer-artist Chiyoko Szlavnics, in documentary recordings by Ensemble Contrechamps designed for various spatialisations by producer Santi Barguñó.

Szlavnics’ work as a composer takes inspiration from her early mentorship in Toronto with the innovatory thinker and creator James Tenney, as well as ongoing studies of Indian Dhrupad practice in the Dagar family tradition, which Szlavnics began learning from Marianne Svašek, and continued in India and the UK with master singer Uday Bhawalkar and his students. She draws psychoacoustically manifesting lines, shapes, forms, and patterns with abstract masses of precisely-tuned frequencies, emerging and receding like breathing. The sounds bear a deep honeyed resistance that could, at any moment, glide into smooth and inexorable momentum, passing through each other like clouds of energy or colliding into explosions of perceptual details. For her, making music is observing the ever-changing manifestations of cosmic clouds, temporally disjunct forces across huge distances cohering in the mind of the listening ear’s act of cognition: beautiful in their ever-changing forms, yet without meaning and without statement.

Both recordings document sound environments that, ideally, would be experienced physically and spatially in real time, the various rationally-connected pitches fusing and moving dynamically in direct interaction with acoustical properties of the sounding listening space. The use of “just” or rational intonation (JI) is central to activating this process, and it marks Szlavnics as sharing a practice that is perhaps one of the key bridges between “experimental-spectral sound composition” in the uniquely North American sense (Partch, Cage, Lucier, Oliveros, Tenney, Amacher, Young, Schweinitz, Sabat, Lamb, Nicholson, et al.) and what I consider to be the one key question of music composition today. Namely: what is the nature and purpose of music in a multilateral, data-driven world in crisis, struggling with historical patterns of exploitation and domination? In tandem with colonial economics, the European classical music establishment propagated 12edo: a standardised system of “perfect pitch” that is at once simple, elegant, useful, and acoustically false. The revival of old-school microtonal tunings in period music practices, along with a rediscovery of older Greek, Arabic, Persian, and Indian systems, marks a return to a pluralism of harmonic and melodic possibilities.

By insisting on strictly realised, exactly tuned relations, and asking musicians to sound these, the composer is faced with a formal dilemma: to stand back from a desire to shape and control the multidimensional material, a wish to make some kind of utterance, and instead to seek an environment within which the sounds may live, unfold, open to being experienced. Tenney recognised this in moving beyond neo-classical strategies and seeking correlations between Cage’s indeterminacy, Xenakis’ formalised music, and Partch’s advocacy of JI based on higher prime identities. In his most seminal JI works: the “Harmonium” series, “Koan for string quartet”, “Critical Band”, among others, Tenney creates an intuitively composed, slowly evolving sequence of chord changes. The music features phenomena: combination tones, common-tone microtonal modulations (changes of fundamental), beating, and perceptual fusion and timbral chimeras created by closely emulating the simultaneous frequencies of an harmonic partial row or harmonic series. Tones emerge from and recede back to silence, or (at times) are clearly articulated, without ornament or modulation (vibrato, tremolo). Time is given on a slow, measured scale using minutes and seconds, allowing synchronised changes to unfold but giving open space for sounds to be “projected” into temporal spaces. This approach allows ensembles of acoustic instruments to play a precisely tuned music and has inspired other composers with a close connection to Tenney, in particular Szlavnics, Sabat, Lamb, and others.

The earlier work present here is titled “Memory Spaces (appearances)” (2017/2023) for fourteen strings, originally composed for the Berlin-based Solistenensemble Kaleidoskop. Credit is given to colleague Thomas Nicholson for his artistic contributions. The open strings of the instruments are transposed to specific microtonal pitches, retaining (with a small exception, a 27:32 minor third in the contrabasses), their usual intervallic pattern of four successive perfect fifths (or fourths). This approach to scordature keeps a natural balance of tension across the instruments, so they accurately produce the desired pitches on open strings and lower harmonics, allowing the players to devote themselves to questions of timbre, dynamics, and blend.

The pitch design features pitches from several harmonic partial rows – C G D A E – up to the 13th identity. In Partch’s terminology, the result is an otonal 13-limit pitch set, but the disposition of harmonic partials in the lowest register means that the common fundamental of all the tones is less than 1 Hz, and therefore not perceived as a unifying pitch. This is a key aspect of how JI is treated in both works: while small number relations may be established between instruments in individual sounds, and relations exist on a local level, there is a deliberate focus on avoiding the “monophonic” unitary aspect of JI where all pitches are conceived and demonstrated from a single common ground.

At the same time, tones are projected with a spectral sensibility, interacting in ways chosen to highlight timbral harmonicities. Higher partials are asked to “nestle” into their lower sounds, creating natural hierarchies that each player must become familiar with. One aspect of the score, the chordal, is complemented by a potential for “melodic” arpeggiation, which is open to interpretation, echoing Morton Feldman’s conception of “Projections” into spatial time-blocks. “The musicians are encouraged to avoid playing ‘on the barline’, entries may begin slightly before or after the indicated time (something like 1-3 seconds earlier or later)… The ensemble is encouraged to develop a collective sensitivity for how each player’s note at any given time contributes to the harmony and collective dramaturgy of each performance. An intuitive approach should be developed during rehearsals, so that the ensemble might dynamically respond ‘in the moment’ to shaping the piece during performances.”

The later, and longer work is titled “Oracles I-V (listening spaces)” (2020/2023) for Ensemble Contrechamps & Bellelay Abbey, which had its premiere performance 29 August 2020 during the international COVID-19 pandemic. The ensemble is a small orchestra of double string quartet and bass, winds and brass without bassoon or trombone, and percussion. The instrumentation was based on a companion work originally planned but not realised due to pandemic circumstances. The composer writes that “the experience of sound in the abbey’s resonant, enormous interior lies at the heart of these five Oracles.” Like a dance performance, musicians are present before the audience enters, and throughout the performance, they are asked to use soft-soled shoes, walking in a calm and unhurried movement. The positioning of musicians, scoring of moving sound, and a distributed audience were key elements of the compositional process, shaping the perception of sound within the abbey.

“Oracles” is a five-part multi-movement work; like “Memory spaces”, it draws on an overtonal JI pitch space, in this case limited to identity 11°, also built from harmonic partials above fundamentals in perfect fifth relations, in this case beginning (Oracle I) with horns and tuba over Bb, F, C, G superimposed with a C-E drone, which is later expanded by adding D and A, anticipated by an earlier appearance of their 5-limit counterparts.

Oracle II features a spatial and density shift to a circle of strings playing unison G evoking the experience of combination tones by adding harmonics and brief phrases of glissandi. Here one senses echoes of Szlavnics’ earlier music with sliding tones, informed beautifully by her experiences as a singer and student of Dhrupad. In conversation, she mentioned to me that the effect of these studies has been to focus her sense that the most fundamental aspect of music, for her, now more than ever, is about experiencing combination tones, a phenomenon Catherine Lamb – also influenced by Dhrupad – also cites, calling it “the interaction of tone(s)”.

Oracle III is a hommage to Sabat’s 1996 work “For Michael Baker”, featuring high trumpets and softly rolling bass drums across a divide. Noticing this and smiling, and then thinking about how my own orchestral music also rolls along the line of fifths from Bb through E made me reflect upon and appreciate how the slow emergence of JI composition in the 21st century is somehow essentially an ongoing, shared work, an unspoken collaboration of many composers passing into younger generations emerging today. We are somehow seeking sound forms and shapes that highlight the uniquely experiential quality of harmonic-melodic rational tuning. In Chiyoko’s words, this Oracle is a reminder of being human, of single, lonely voices in a vast space or cosmos. I feel this image of loneliness in a context of poetically imagined collaboration is, in some way, another personal touchstone; here I remember Walter Zimmermann’s beautiful “Desert Plants” conversations in which this theme is so poignantly illustrated over and over again.

Oracles IV and V return to a more abstract spirit, highlighting the movement of sound via single notes and brief two or three note chords, finally reaching a high “cluster” on the dyad C#-D, activating “a dynamic shimmering of complex sound”.

MARC SABAT

CREDITS

Recorded at

Bellelay Abbey, Switzerland

October 2023

Composed by

Chiyoko Szlavnics

Performed by

Ensemble Contrechamps

Susanne Peters, flute

Valentine Collet, oboe

Laurent Bruttin, clarinet 1

Marie Mercier, clarinet 2

Charles Pierron, horn 1

Clémence Lion, horn 2

Paul Hübner, trumpet 1

Mathilde Conley, trumpet 2

Serge Bonvalot, tuba

Thierry Debons, percussion 1

Sébastien Cordier, percussion 2

Maximilian Haft, violin 1

Madoka Sakitsu-Lapeyre, violin 2

Jesus Manuel Larez Leon, violin 3

Rada Hadjikostova, violin 4

Matteo Cimatti, violin 5 (only for Memory Spaces)

Patrick Schleuter, violin 6 (only for Memory Spaces)

Hans Egidi, viola 1

Vincent Hepp, viola 2

Anne-Laure Dottrens, viola 3 (only for Memory Spaces)

Martina Brodbeck, cello 1

Jan-Filip Ťupa, cello 2

Aurélien Ferrette, cello 3 (only for Memory Spaces)

Jonathan Haskell, double bass 1

Noëlle Reymond, double bass 2 (only for Memory Spaces)

Max Murray, conductor

For Eva Hesse

Quadraphonic mix for Bellelay Abbey made at the Studio for Electroacoustic Music, Akademie der Künste Berlin, 2023.

Played and re-recorded in 3D at Bellelay Abbey.

Contrechamps artistic direction

Serge Vuille

Executive production

Elisa Charles

Stage manager

Florian Guex

Just intonation assistance

Thomas Nicholson

Liner notes

Marc Sabat

Video shooting

Scott Vuilleumier

Recording

Santi Barguñó, Hugo Romano Guimarães

Mixed and mastered with

ATC Speakers

Graphic art direction

Lorena Alonso

Produced by

Santi Barguñó

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Antoine Françoise, Julien Annoni, Fondation Abbatiale Bellelay, Canada Council for the Arts.

Memory Spaces · Album images

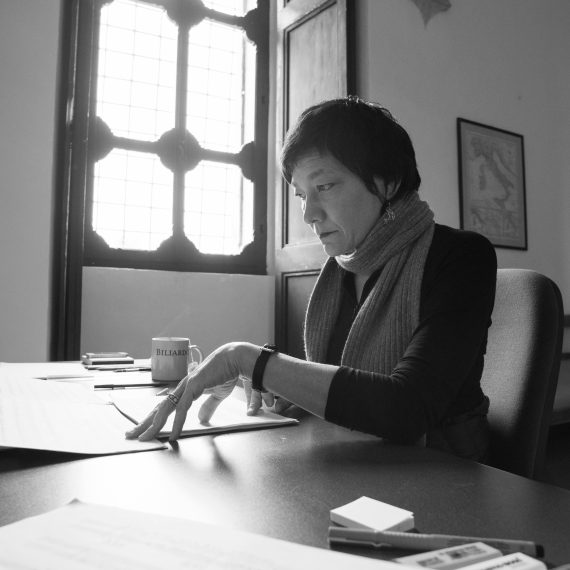

Chiyoko Szlavnics, Ensemble Contrechamps, Max Murray, Memory SpacesChiyoko Szlavnics · Photos

Chiyoko Szlavnics, Memory SpacesRecording Memory Spaces · Photos

Chiyoko Szlavnics, Ensemble Contrechamps, Memory SpacesREVIEWS

“The work of Berlin-based Canadian composer Chiyoko Szlavnics is marked by exquisite care and detail—a harmonic world that relies on instrumental precision to summon harmonic splendor. She spent a long time working with Geneva’s excellent Ensemble Contrechamps to master the two marvels contained on Memory Spaces, her first portrait album in eight years. The wait was worth it; nothing I’ve heard this year has pulled me so strongly to another sonic realm.” Read here

The Best Contemporary Classical Music.

BANDCAMP, Peter Margasak

“Una experiencia sonora que trasciende la mera escucha. Sus obras son paisajes que respiran en el espacio, y este disco, con Ensemble Contrechamps bajo la dirección de Max Murray, lo documenta con cuidado, radicalidad y profundidad.” Read here

REVISTA RITMO, Joan Gómez Alemany

“Das ist eine Musik, die im physikalischen Sinne gedacht ist, eine akustisch informierte Musik, die sehr genau auf ihre Entstehung rekurriert, auf die physikalischen Phänomene, die eine Rolle spielen und die mit traumwandlerischer Sicherheit gesetzt ist. Und diese Aufnahme finde ich auch unglaublich toll — dieses Direkte, das sie hat. Man kann sich einklinken und jeder kleinsten Nuancierung folgen. Das fand ich sehr, sehr schön.” Listen here

SWR, Martina Seeber

“Memory Spaces is an album that reminds me what it was that i fell in love with, so many years ago, when i first discovered Chiyoko Szlavnics’ music. It’s that sense that nothing is as it seems, everything familiar has been reconfigured, reimagined, reconceived. Where so much music using non-standard tunings is just fussy, neurotic and joyless, Szlavnics’ work demonstrates a contrastingly genuine emancipation, one that feels effortless, and sounds timeless.” Read here

5:4, Simon Cummings

“El sello Neu Records está tomándose su tiempo, amasando uno de los catálogos más inspirados y atractivos de música contemporánea (con toda la literalidad del término: de aquí y ahora). Conjuga discos de carácter sonoro más osado (Fritz Hauser, Octavi Rumbau) con otros de una estética marcadamente actual, pero de escucha más canónica (Jürg Frey, Joan Magrané). Este que ahora presenta, dedicado a la compositora canadiense Chiyoko Szlavnics (1967), caería del lado de los primeros y, a decir verdad, era cuestión de tiempo que su música se pusiera bajo el foco de la casa. Primero, por la calidad de su obra y el interés que esta suscita; segundo, por cómo la creadora se acerca al sonido como materia prima pura que apenas violenta, en la senda de Alvin Lucier y Éliane Radigue. El Ensemble Contrechamps (prodigioso coprotagonista en el “mejor” disco de la colección de Neu, aquel dedicado a Bryn Harrison) se encarga de las dos piezas espacializadas: Memory Spaces y Oracles. La reducción a estéreo, trabajada meticulosamente, es prodigiosa por cuanto estos volúmenes sonoros de presencia casi física se mueven ante y entre nuestros oídos…”