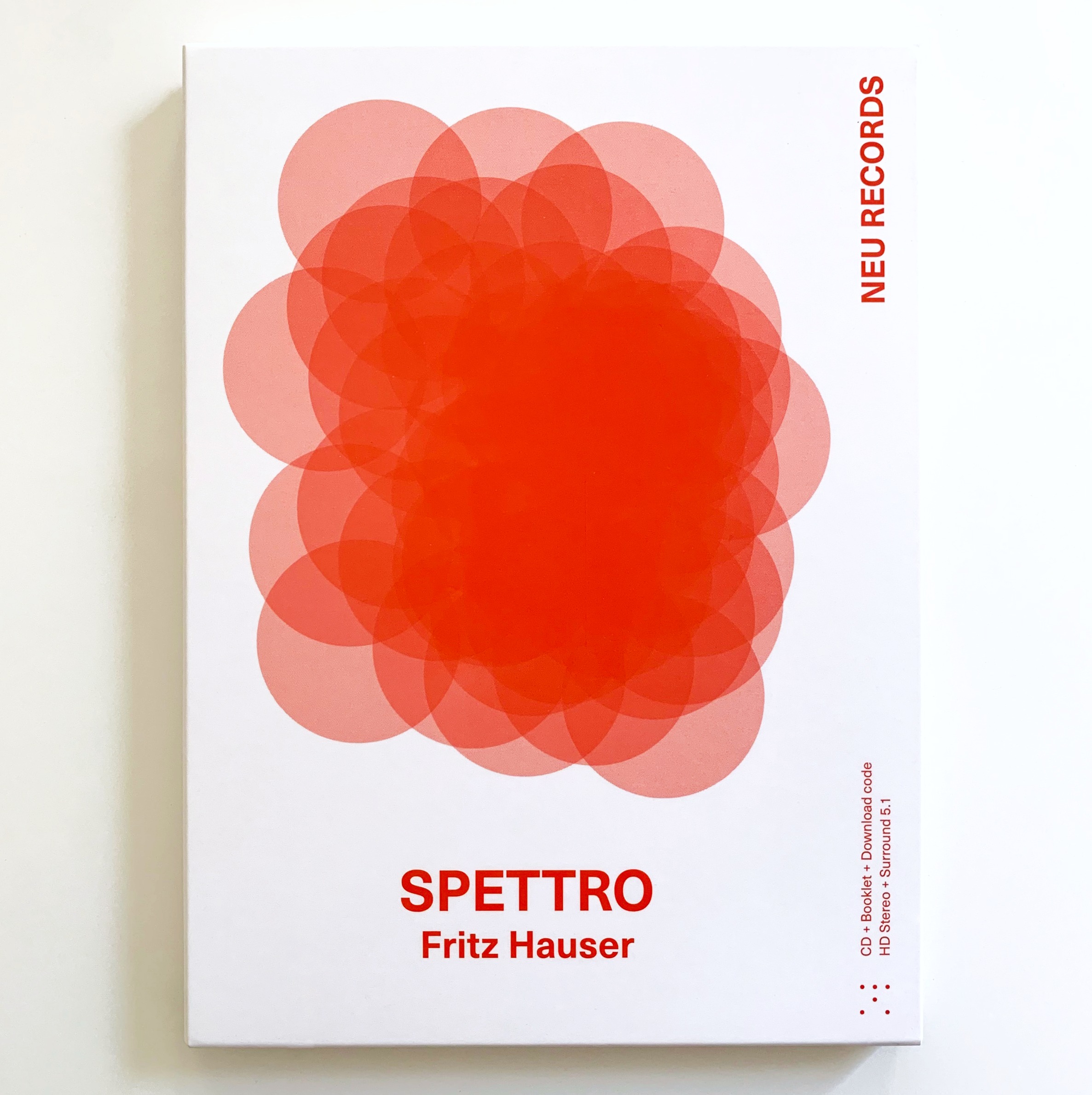

SPETTRO

SPETTRO (2018) — 45:31

IMPROVISATION 1 (2019) — 5:30

IMPROVISATION 2 (2019) — 8:09

IMPROVISATION 3 (to Fernao) (2019) — 7:54

SHONG (2017) — 11:20

Fritz Hauser, drums and percussion

Barbara Frey, director — Spettro

Total time: 78 min.

Recorded in 3D format for sound installations (5.4.1), surround sound (5.1) and stereo (2.0)

World Premiere Recording

BUY ALBUM

CD + Booklet — HD Digital format included — 21,90€

HD Digital — Stereo. 24bit 96kHz — 14€ (Surround 5.1from June 2021)

Digital — Stereo, 16bit 48kHz — 10€

More info about formats here

SPETTRO — outside in

Spettro is a ghost conspiracy for solo drums. The piece begins with a driven pulse, subtly altering the audience’s perception of space and sound, leading into mesmerising percussion landscapes, using density and silence to denote rage and calm, and enchanting with humour and subtlety. The performances of Spettro are intensely alive. Barbara Frey (director), Fritz Hauser and Brigitte Dubach (lighting) once again succeed in bringing into being a new cosmos through sound and images with the simplest of means. Where Drum-with-Man took reduction to the extreme, Spettro leads into an oscillating fantasy.

Characteristic of Fritz Hauser’s Spettro is the deliberate restraint from which abundance then grows. The Swiss percussionist and composer Fritz Hauser relies on apparently simple gestures, uses minimal instrumentation, lets the silence work –and thus creates narrative arcs of great coherence and percussive conciseness. His sound explorations are always precisely planned and yet grow from the moment.

The world premiere of Spettro took place during the Lucerne Festival on August 26, 2018, in the large concert hall of the KKL. Fritz Hauser was Composer in Residence at the Lucerne Festival in the summer of that year. Further performances followed in March 2019: Gare du Nord, Basel; Museum für Kunst und Geschichte Freiburg (MAHF); Schauspielhaus Zürich (Pfauen). In August 2019 Spettro was performed at the Casa della Masche in Bionzo, Piedmont, and then at the headquarters of Kraftwerke Zervreila AG in Vals. Especially for this event in Zervreila, electricity production was stopped for a few hours. At that time, Hauser was playing with around 100 million cubic metres of water behind him, the latter held back by a 151 metre high arch-gravity dam.

SPETTRO — inside out

The drum has long been regarded as the bearer of diverse messages, as well as a vehicle for voyages to the underworld and upper-world –witness the drums of the shamans. Similarly, Fritz Hauser’s playing is characterised by the instrument’s acoustic dimension being expanded in inimitable fashion. Doors to unknown worlds are thrown open, ‘memory spaces’ are revived. Spettro could be termed an association generator, shaping our perception by means of an astonishing variety of timbres and unusual sounds, time and again transforming what we have already heard.

Spettro begins with a long sequence of precisely held drumbeats, which seem almost incantatory. Who or what is being summoned here? Could it be a spirit world or spirit beings and their symbolism, as the title of the work might suggest? The ghosts are in any case already peeping out from behind the drum, whatever was lurking in the background forges ahead into the foreground, a metallic shimmering is unfurling, on the distant sound horizon a few muffled shots from field guns of bygone wars are audible. The victims of battle, now animate, stir their stumps and infiltrate our perception. The dark, deep rumble gains intensity, soldiers’ boots marching on the road to nowhere. A solitary high and hollow sounding bell –was it the bell that called them to war back then?

More and more metallic sounds mingle into the action. The admonitory striking of thick knitting needles on balcony railings is transformed into a steady beating on pots and pans, the protest gains in force, discontent finds its sonorous reverberation, before swiftly levelling off. Then ensues a ticking that is not in second intervals, as if the clock of life had been readjusted once more; the space-time continuum undergoes a curious shift. The echoing ring becomes softer and begins to shimmer, overtones steadily gain ground, before the stroke of the gong causes the oscillating sound-clouds to come crashing down.

The soundmaster has called the spirits; now they answer. They reveal themselves as if calling from beneath the water’s surface, akin to mysterious whale sounds. Or are we on the high seas in a ship’s hull?

Suddenly, however, the spirit beings openly, or only seemingly, change the setting and gather in a large, sweeping castle hall. A ritual with pellet drums starts up, bantering skirmishes erupt here and there, there is flirting and coarse jokes are made –and these little balls curl repeatedly pattering on the leather, but no drummer is to be detected in the imaginary castle hall. A crescendo on the drums rears up, followed by the big thundering drum –abrupt change of scene. The sound of this ghost sonata takes on an almost ethereal quality –fleeting, like life itself. Tick, tock, tick, tock… memento mori. Chimes in the light wind strike gently against the trunk of the tree they hang from. The giant, suspended gong starts vibrating, profoundly evocative overtones fill the room and let Spettro gradually die away. The dark, wafting, lingering echo of the last gong stroke carries us into nothingness.

Adrian Vieli, June 19, 2020

IN CONVERSATION

Ghost sounds or Hansel and Gretel hanging off the north face of the Eiger

Following on from the Drum-with-Man programme in 2001, in 2018 percussionist and composer Fritz Hauser developed a second solo programme entitled Spettro, in collaboration with director Barbara Frey. The premiere took place on 28 th August, 2018 in the KKL concert hall in Lucerne, while Fritz Hauser was composer-in-residence at the Lucerne Festival. Mark Sattler, literary advisor and head of contemporary music projects at the Lucerne Festival, conducted the following discussion with Fritz Hauser and Barbara Frey on 13th August, 2020 via Zoom.

MS: (Mark Sattler) How did the genius loci of your house in Piedmont, the spirit of the place, influence the creation of Spettro?

FH: (Fritz Hauser) We didn’t start working on the project there, but tried things out initially in the music studio at the theatre in Zurich. Then over Easter 2018 we finished putting the piece together in my house in Italy, the Casa delle Masche. It’s a place where you can really delve deep into things because it provides the right acoustic and focus and it gave us a decisive impetus. We thought up a diverting game where the spirits who live in my house get up to all kinds of things – especially musical things, of course – when we’re not around. It was partly about making these things audible.

MS: So was the title Spettro fixed from the beginning or did it come later?

FH: It came later on quite spontaneously. Spettro means spirit, but also means spectrum. Since we also wanted particularly to depict sound spectra with the percussion instruments I found it pretty appropriate.

MS: How did you select the instruments?

FH: Barbara, who’s a drummer herself, had the idea of working with a big gong, a tam tam. A gong like this sounds great, but after a while it’s had its effect, unless you want to do a really long crescendo on it like James Tenney did. So we started to play on its suspension frame and that’s when all these resonances came about: the gong became a resonating body, created a reverb. That completely fascinated us and we did a lot of research into it. When exactly the drums were added, I can’t even remember. Do you recall that, Barbara?

BF: (Barbara Frey) I don’t remember. And for me it’s always a very good sign when I can’t recall how something came about during the work process. It’s a bit boring if you work through something and then just check it off. We knew from the beginning that we didn’t want to rehearse like that. I just know that this developmental process was very organic. Nobody had a head start. We were on a par and then like Hansel and Gretel we went off into the forest together to see what would happen next.

FH: I know that already back in Zurich we were not only busy elaborating mysterious sound paintings, but also wanted to come to terms with the rhythmical aspect. It’s actually always about finding ways to be radical, if you haven’t been so from the beginning and gradually trying to shape thoughts in such a way that they make sense and gain strength.

BF: Exactly. It was about how to create pulsation. How you then effectuate this pulsation, with which instruments, how it’s doubled, quadrupled, halved and so forth, that’s the next step. And we wanted to create something continuous. That there are different parts in the middle and right at the end is due to the development. The pulsation was important to us; that was the egg we laid together.

MS: Right from the start of the piece you can hear something grumbling inscrutably in the depths alongside the regular pulsation. Where do these ghostly sounds come from?

FH: The beginning of Spettro is a leap into the heart of the matter. But the pulsation is not rigid, there are continual modifications in the dynamic and the sound. You can’t get a precise grip on it. And because it’s playing on several different levels at once and the resonance of the room is a further factor, you ask yourself: is just one person playing or are there several of them? What kind of instruments are there? Where do the basses come from?

MS: And where do the basses come from?

FH: From two, big, foot-played bass drums, equipped with very soft beaters, so that you can hardly hear the attack. Of course the drums also vibrate along even without me playing them. At the beginning I do a sort of very quiet dance down there. After a while it gets louder, single beats, then sometimes doubled. It’s never a continuous, straight rhythm, but rather the resonating sounds of two bass drums, like a murmur, a soft thunder, a constant, accompanying vibration. The tam tam has the function of a large reverb plate for everything that happens up front. It’s actually there right from the start, though it’s only played in two spots, with a superball, a broom and, at the end, with the big, heavy mallet. These are finely chiselled things: we don’t bang on the tam tam, but rather elicit different kinds of resonance from it.

MS: Would you agree with the following statement: Spettro takes off where Drum-with-Man ends? Drum-with-Man is the child playing with the drum and mastering it. Spettro is the percussionist, the adult, who’s drumming. At some point in the course of the piece the percussionist stops drumming and listens to the spirits, then dives into the spirit world – breaking through the ‘other door’.

BF: That’s funny, that wouldn’t have occurred to me now. I’m opposed to seeing any logic or coherence in it. Both Drum-with-Man and Spettro include small children right through to old people. For me the decisive factor is what I experience in the work with Fritz; the sounds arise out of this work. We experiment together and try out different sounds, above all listening to each other, reacting to each other, continually conversing. That’s actually what is crucial in this weird form of solo programme, where a percussionist is sitting alone on the stage. The point is to make the dialogue visible, that’s how I’ve always understood it. And I couldn’t say now if there’s a certain development from A to B. It might as well be exactly the other way around.

FH: Whether it has a narrative dramaturgy in the sense of one thing following another, or whether one could put it all together differently is not something one can say in retrospect with any accuracy. All I know is that we did different scenes, we liked one scene, we didn’t like the other one so much and then left it out, but then maybe came back to it later on because it suddenly made sense in another context. This is actually what instant composing is. When I work with Barbara, we often create images that we don’t tell anyone else about. They’re like working titles for certain scenes, for example ‘apricot cake’. It has nothing to do with apricot cake, but we know exactly what we mean by it, a certain feeling about the action, a certain state of mind. I need these images to find myself again. I find it dull when I’m told to develop a crescendo a little more slowly. Of course that’s the technical consequence, but if I’m told that the sun should rise a little more gradually or that the night should spread out a little more slowly, then I can deal with it better than with a purely technical instruction. Barbara provides good impulses there. She also doesn’t turn up at the start with a ready-made directorial concept and say ‘So this is how it’s going to be’. We’ve known each other for a while and like this we can get involved in the process together. It takes time, you have to listen a bit, you have to build up energy again and again, dialogue with one another, and then suddenly something happens that brings great delight. Barbara is very good at this. I have also experienced it with her while working in the theatre: she guides the cast in such a way that nobody goes home totally discouraged in the evening, but instead we all keep working at it until it’s clear it will continue to develop in an inspiring way.

BF: It’s gratifying of course that you experience it this way. We perceive ourselves very differently and are unaware of the effect that we have on others. But I wanted to say something about the spirits: the part with the funny little African hand drums, the ones with a sort of face and plaits. That was never in order to have some sort of optical effect. It would have been terrible if we’d intentionally looked for a way to represent the ghosts visually. It was never remotely about the visual aspect, it was about sound. And that’s why the ghosts were there for me right from the start, because everything we hear and all the sounds we produce ourselves have a kind of other world. Making this other world audible, with these wonderful, resonating instruments, whose sound lingers in the air and undergoes transformation, is actually the ghostly aspect that appealed to us. The whole point about ghosts is that you can’t see them (except in a second rate children’s book). Take the household spirit called Schuggi: he got sucked up by a hoover. Schuggi was all white, just how you’d typically imagine a ghost, white as a sheet. He got sucked up and came out black, but it wasn’t that we actually went looking for Schuggi, I think.

MS: But still it’s very unexpected when the African hand drums and the roaring lions emerge after the build-up with the pulsations. The mood is suddenly playful, just like when you both played and improvised with toys and other bits and pieces at a table in the art museum in Lucerne, when Fritz was composer-in-residence. I hear a new dimension unfolding during the episode with the African hand drums, the plastic tubes and the roaring lions, where this mood of utter playfulness, completely at odds with the pulsations, begins about thirty minutes into the piece. And that is why it suddenly makes me think of a narrative dramaturgy, akin to a radio play.

FH: I wouldn’t deny that. I think my music always has something imaginative and image-inducing somehow. Even when I remain radical, as in the case of Schraffur, for example, I still create soundscapes: people are on the move, they travel by train, they walk, they swim, they fly, they see images. The drums have a great advantage over other instruments: they don’t produce familiar melodies and conventional harmonies. It’s a bit like going to the theatre in Russia. You don’t understand a word and you depend on facial expressions, postures, tension between people to put together the story. So you’re not burdened with language, you can listen to the voices in this abstract space in a completely different way. That’s why I’ve told singers in various music theatre projects to leave out the text. I want to hear the sound of the voice. The moment a singer sings a word or tries to form a sentence, I’m actually taken away from the music, I’m in the narrative, in the text, and then something switches over in my brain, I’m no longer in this abstract sound world. How would it be if I were to give a concert and turn to the audience before the first beat and say: “When you see these instruments, how do you imagine they’ll sound?” With percussion everything is completely open and the combination of instruments creates a new spectrum – Spettro – each time and we plunge into it and find ourselves without any point of reference…

BF: I think that’s very important. We’re without any reference point. We find the pictures afterwards. It’s not as if we’re looking at pictures and thinking, “Oh, now the spirit could totter in there” or something – that would be banal. Instead we hear what happens, what happens to the sound and then suddenly pictures emerge, but we don’t start with the pictures. Otherwise it would run the risk of being kitsch or a bit complacent. The starting point has to be the pure sound and the fascination when you suddenly notice for example that you’re playing with knitting needles on the frame and the gong is sounding all the while. We didn’t ask it to do so, it just does so it of its own accord. I think this was an essential aspect of the project: you discover things that just seem to happen. It’s like with the ghosts: you don’t have to call them, they’re just there.

FH: Exactly, the pictures only come afterwards. Sometimes it irritates me when composers come to me and ask me how they could write this or that. That means they don’t really have any idea of the sound they want to create, they just have a concept and have to colour it in. The work that Barbara and I do develops organically, because we deal with the instrument differently, because we know the instrument inside out and are willing to experiment. Then we discover something and we can always stick a label on it or tell a story about it afterwards. But the crucial thing is that it’s created organically, not through a predetermined concept or script.

BF: There’s another interesting point I’d like to make, when I look back on a long-term collaboration like ours. We’ve been working together for over thirty years and have been friends for thirty-three years. Over that time one also collects, so to speak, a shared store of spirits. When I’ve just got to know somebody, there’s little chance of having such an extensive spirit realm in common. The longer you know each other and the more you move within a dynamic like this, witnessing one another’s low periods, or even experiencing together how other people leave, disappear, are simply no longer there, about whom you continue to talk –this accumulated biography also means having more ghosts in common. It’s something one cannot really discuss. But it’s there and it washes over you leaving its mark, and it’s actually the most interesting aspect of this kind of work. If I had created this piece with someone I’d never seen before in my life, it would have turned out quite differently. And vice versa, I dare say for Fritz: with another director, something completely different would have taken shape. I think that after all these years there is a mutual, unstated, bizarre world behind it all that you share. It’s via this common space of thought and sensation that these spectres or ghosts pop up. That’s actually pretty organic. It also includes hanging on in there together when we don’t know what’s coming next. For me that’s the central quality of forming this sort of association, whether in twos, threes, fours. In our case it was now just the two of us, and in this alliance it’s absolutely permissible and actually necessary that we don’t know what will happen next. If we know in advance then we shouldn’t be doing it.

FH: For me there is always this fear in the creative process that maybe you’ll never come up with anything again. But really to let yourself fall into this hole and to fish wholeheartedly in troubled waters, that can be a wonderful moment. I know for a fact: we’ve never manoeuvred ourselves into such a stressful situation that we’ve found ourselves at a loss on the day before the premiere, unclear about where we’re headed. Barbara is also not the kind of director who says after the dress rehearsal that we have to start all over again or throw out three of the scenes. Instead we draw on a basic knowledge that’s been gained earlier in the rehearsal process. We can rely on one another.

BF: And it’s also good to have a laugh together now and then about the things that just didn’t work. People don’t imagine –how could they?– that you produce a lot of rubbish. While you’re staging a production, while you’re creating something, you produce an insane amount of useless material. You focus on something for a long time, you think it’s exciting and then suddenly you realise that it’s not exciting at all, it just doesn’t have any power, it’s like a bad joke. And of course you couldn’t have realised it earlier on, because you were enthusiastically throwing yourself into this blind alley. And I think that’s very important and that is of course when something precious and luxurious is involved –don’t get me wrong– it’s fine that there’s superfluous material being created which is then discarded. You don’t have to concentrate from the outset on increasing efficiency or maximising benefits, but instead for once all you have to do is to listen. And that’s of course a huge privilege that you wouldn’t want to miss.

FH: One of my comrades-in-arms, the architect Boa Baumann, put it in a nutshell: when you work with Barbara, you sound better than usual. That has to do with the fact that you need a counterpart in this work. You need the feedback, especially when leaving familiar terrain behind you.

BF: So it’s actually that recurring feeling of hanging off the north face of the Eiger together, that’s what really counts. You can ask yourself the question with whom in your professional and private life would you like to hang off the Eiger north face and see what implications that has. Over the years I have developed this feeling that I can well imagine hanging off there with Fritz. I have the impression Fritz feels the same way.

FH: Yes, that’s just how it is. I’ve always compared making music or being creative to mountain climbing: you can be intricately prepared, but the crucial things remain instinctive and are organic to the whole undertaking. There are many factors involved that you can’t influence. It’s the journey together that matters, not the destination, because you can rely on the fact that the other person will support you when you start to skid and that you will always be taken seriously, even if you’re losing it or if you stop concentrating. That’s all part of it.

MS: Barbara, can you describe a particular moment or give us an example of something that you’ve passed onto Fritz, that he found enriching, despite his clear autonomy and independence?

BF: Well of course that’s hardly something I can say, you’ll have to ask Fritz. I don’t know. But now we’re on this subject: unlike Fritz, I can’t do anything alone because I’m a director and theatre manager. I envy and admire writers, painters, musicians. I don’t exist without others; I only function through and with other people. Whether that has an effect and what that effect might be, I can hardly say and of course I can’t control it. If I control it, then the collaboration wouldn’t be good. I don’t find directors who are control freaks and want the people they work with to be an extension of themselves very interesting. That’s not my world at all. For me it’s more about reciprocity. That’s why I’m absolutely dependent on other people and as to what exactly my effect is or isn’t, you would have to ask them.

MS: Let’s ask Fritz then: what did Barbara impart to you during your collaboration? What did you pick up from her, what do you owe her?

FH: There are two or three important things. One is listening carefully, and especially that when she hears five things at once she has the ability to pick out the key thing. Also the fact that she discovers some resonance in the whole thing which makes sense not only musically but also dramaturgically. And she can also pinpoint where something important happened, where there has been a certain energy. One particular scene springs to mind: while working on Drum-with-man, I usually improvised in the morning, half an hour, forty minutes, just a menu du jour, as we musicians call it, just giving vent to something that you experienced the night before. Barbara would sit there with her book and make a note every now and then. During one improvisation there were passages that I found impressive, purely technically. But she wasn’t interested in that at all. She sat there like this and when it was finished, she looked at her notes and said: “At seventeen minutes, there was something there”. And then we tried to reconstruct what had happened seventeen minutes into the impro. That was really a point of total hopelessness. I got all tangled up, I really didn’t know what to do. But I also knew that it was too early to stop, we had only just started, we had to go on. And then this energy of desperation appeared. It’s actually where friction, heat and resistance arise, which ignite the creative spark. These are the things music is all about: I’m not interested in producing elegant melodies, but in playing in such a way that you’re creating a friction within yourself, between you and time, between you and the sound, so that an energy field is created. Barbara can listen to this pretty precisely and act as a guide. And the other thing is that she’s very good at teaching me to be patient.

When you work alone, you tend to do things a bit too fast. You think, okay, I’ve heard that now, I know that’s possible. Then Barbara says, “No, no, no –wait! That’s far from being played out! What’s happening here is just one sensation and there’s a second sensation still to come.” She supports me in developing the feeling that, yes, this can be done again, and then it can be done once more, and then you add the other hand and the energy is continuing to flow. She’s extremely precise, Barbara, you can’t pull the wool over her eyes. She knows exactly what she wants and exactly what she doesn’t want. That’s great. I’d say Barbara is my third, fourth and fifth eye and ear. At the end of the day she’ll say: “That’s good now.” Then we’re on the right track.

MS: Keywords: efficiency and quality. This form of working process and collaboration that you describe has little or nothing to do with the quantifiable efficiency of a cultural industry that only allows things to happen if they cost so and so much and if everything is encased in measurable parameters. What you describe as luxury: the time needed for the creative process, the particular person who will enable the right chemistry, is quite at odds with that.

BF: The definition and perspective of what luxury has to do with it is pivotal: I think that at this particular time, where so much is not possible due to the pandemic and distancing, we should not become too modest as a result. Culture, all cultural creativity, cultural life and experience are all suffering at the moment. [This interview was held in August 2020, when there were still massive restrictions on cultural life due to the Corona pandemic. Note M.S.] And I think you can see that what we do is not a luxury at all, but is absolutely necessary for a large number of people. It’s something we should defend, and we should guard against politicians who like to imply cynically that some of our culture is just a luxury. What we do is never luxury in the sense of superfluity. It is vital so that that we can objectify the world, think about it in a different light and reconnect with it in a new way.

FH: For me it is a luxury to be able to shape my profession the way I wish to. And that’s why I want to fight for it, come what may. I have arranged my life in such a way that I can afford it. Well actually I can’t afford it, but I’d like to be able to afford it. We have to afford ourselves this luxury. I recently gave a concert in the Forum Valais with a young drummer, Julien Annoni. We played four pieces of mine, two as a duo, two solo. We went to the Valais, rehearsed for two days. We set everything up, rigged up the lighting. The fee was so ridiculous that we couldn’t even pay our expenses. There were twelve people there –and it was an amazing concert. The collaboration with this young musician was perfect. We told the organiser that Julien Annoni started playing percussion because of me: his aunt took him to a concert of mine almost twenty years ago. Ten years later I was his examiner at the conservatory in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Then he became a member of the group we spoke who recorded a CD of my music (Different Beat, Neu Records) and I do programmes with them, like at the Lucerne Festival. And now we are playing as a duo. I am twenty-seven years older than him, I could be his father, but it doesn’t feel that way. We were on stage and the organiser was very touched, and said to me: “It’s great that you’re on for this.” Yes, we’re a duo, we work on sounds, we try to get it right. Actually that’s all it is and that’s what it’s all about! If I can’t do it like that, then I don’t want to do it. This is a passion that cannot be pressed into cultural and bureaucratic regulations. Nobody can take me away from it and it’s too late now anyway; I’m too old now, I’ll just keep on doing it. It works fine just as it is!

Slight Return – 3 Improvisations and Shong

MS: The improvisations that you recorded for Spettro in that great concert hall in Saragossa make me think of Jimi Hendrix, who after an early morning session, goes back into the studio and records this brute version of Voodoo Child, known as Voodoo Child (Slight Return). Just after recording Spettro, you played and improvised with an extended range of instruments in the same room.

FH: We’d planned two recording days. Spettro is not made up of individual takes, which is what the music producers Santi Barguño and Hugo Guimarães are used to when recording chamber music ensembles, where countless cuts are made every minute. They were blown away: here comes Hauser, sets up his stuff and does version one of Spettro. I have played other versions since, but the first one was it.

I love it when I can go back on stage after a concert and just improvise a bit for myself. Then I’m supple and warmed up. I know how it all sounds, I don’t have to prove anything anymore, I can just play. That’s how I did it.

I wrote Shong for a fellow percussionist, Louisa Marxen. I took this old Leedy snare drum, which I got as a gift from a drum manufacturer in Basel, with me to Saragossa. The drum genuinely once belonged to the legendary American jazz drummer, Gene Krupa. It’s bigger than a normal snare drum, 15″ in diameter, and it’s made with natural skins. At the beginning when the pulsation started up and I slowly took the pressure off the skin, this incredible sound space was created in the Mozart Hall in Saragossa. You heard the basses more and more with each beat and a sort of drum-in-space was created. I think Shong fits in well with the improvisations.

MS: Yes, one has the feeling that the beginning of Spettro is Shong.

FH: If so then the other way around: I wrote Shong later, in the autumn of 2018.

There’s a funny story about Shong: I composed the piece for Louisa Marxen, a percussionist from Luxembourg. She told me that she’d been inspired to play the drums after hearing the Hämmelsmarsch. This is part of the Luxembourg carnival tradition, a ritual with a lot of drumming, which fascinated her as a child. So I researched it on the internet and came across a youtube video of a little boy with a drum, who starts drumming out of pure playfulness, completely uncoordinated. You can tell that two sticks are a bit much for him, and then he throws one away and just plays with one stick. So I decided that Shong should be mostly played with one stick. Like this I subvert the expectation that two sticks should be used for drumming. Later on I do use brooms and so forth, but at the outset it’s just this one stick and it opens up whole new possibilities with dampening and letting the drum sound. For the title I invented a cross between sheep and song. Sheep because it’s called a Hämmelsmarsch (Hämmel being a male sheep) and Song because in the last part of the piece the player has to sing.

Two months ago an Australian friend of mine played Shong in Sydney. He’s been working for many years with the group Taikoz which specialises in Japanese drum music. He told me he wanted to put together a solo programme, and I said that I had a new solo piece for snare drum called Shong. He was immediately enthusiastic, because Shong in Japanese refers to a kind of state of meditation. I didn’t comment on that (laughs).

So my Australian friend transported the title Shong to Japan, to some Zen Buddhist monastery, while the inspiration for it actually came from a Luxembourgish drum tradition. I like these curious connections that pop up.

MS: I was looking at the sheet music of Shong and I noticed something interesting about the notation –you jot it down when the hand position or the stick changes– it’s all specified. But it doesn’t say how exactly it should end up sounding and probably that can’t be written down. And this brings us to what Spettro is actually all about, how, thanks to the pulsation, you elicit resonance from the instruments in the background and the big gong… sounds that aren’t noted down in the score. I find that really interesting.

FH: That’s also the main issue when you compose for percussion. The choice of drum is crucial, especially in such a simple piece. Like in the dialogue between the instrument and the surrounding space, which is so important for me in Spettro as it is in Shong, but which cannot work if you don’t know your instrument.

CREDITS

Recorded at

Auditorio de Zaragoza, Spain, July 2019

Composer and percussionist

Fritz Hauser

Music Production and Sound

N · Santi Barguñó, Hugo Romano Guimarães

Liner notes

Adrian Vieli, Mark Sattler

Graphic Art Direction

Lorena Alonso. Estudio Gerundio

Video

Guillermo Barguñó

Mixed and mastered with

Dynaudio speakers

Fritz Hauser plays

Zildjian Cymbals

Produced by

Santi Barguñó

REVIEWS

“Spettro is a positive litany in uncertainty and ambiguity. (…) Like an impromptu drum solo blown up to gargantuan proportions, Spettro taps into – as its name in part suggests – a full spectrum of percussive possibilities, not merely blurring but embracing and merging the austerity of ritual and arbitrariness of play into a complex, disorienting whole. “ Read here

5AGAINST4

“Spettro, diu Hauser, és una trama fantasmal per a bateria en solitari. Nosaltres aniríem més enllà, perquè considerem que el tractament del so de la percussió és espectral, policromàtic, insistent i hipnòtic, i que busca la inestabilitat de freqüències i superposicions d’un sol tema (i d’una sola història), amb frasejos narratius extremament concisos que furguen febrilment les nostres percepcions.” Read here

Fritz Hauser: Spettro

Fritz Hauser: Spettro